This is a new series on The Set Pieces in which Adam Hurrey casts his eye over the numerous attempts to depict football in films. You can read the first instalment, on When Saturday Comes, here.

Synopsis in 140 characters

Cocky copper infiltrates hooligan firm of future soap stars but sees his life fall apart as the boundaries begin to blur beyond recognition.

The hooligan film is a curious corner of the football genre. Alan Clarke’s TV drama The Firm (1989) was the first dip of the toes into a sub-culture that plagued the English game at the time – Gary Oldman’s Bex Bissell setting the benchmark accordingly – but the big screen would eventually see some increasingly cartoonish depictions of football hooliganism.

The Football Factory (2004) was swiftly followed by Green Street (2005), the utterly absurd – and therefore very watchable – mess of bad accents, posturing and Elijah Wood. But, somewhere in between Oldman’s simmering fury and Wood’s wide-eyed West Ham education, lies an undeniable classic.

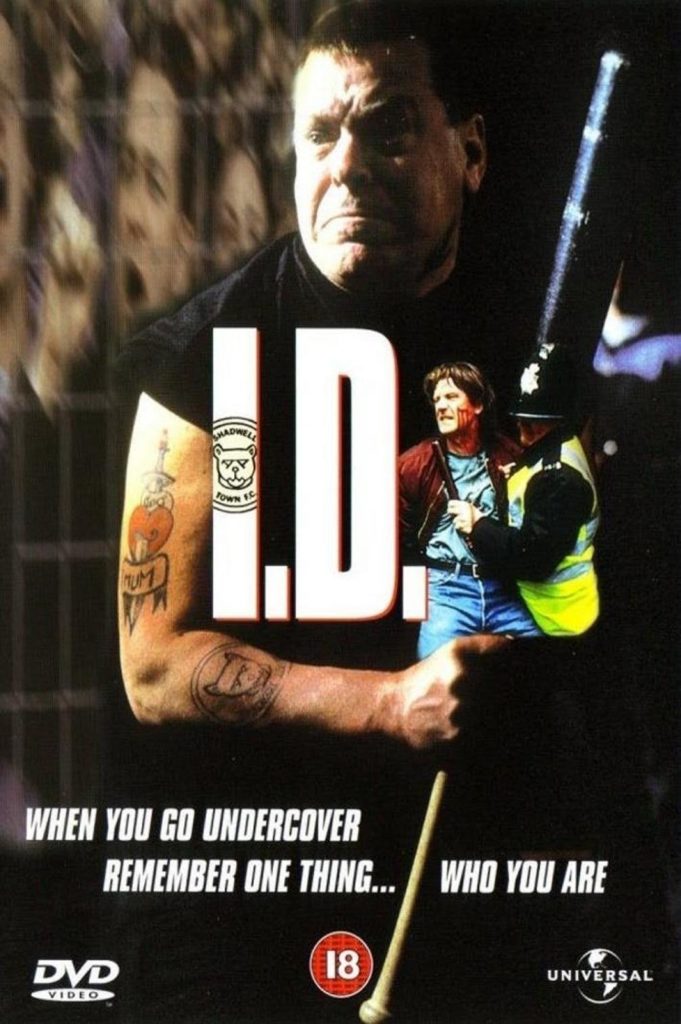

Let’s get this straight from the outset: I.D. (1995) is a superb film. Not from a purely critical perspective – unless a nomination for the Golden Alexander at the 1995 Thessaloniki Film Festival counts – but there is a perfect bleakness to it to underpin all the tightly-spun testosterone.

There’s virtually no actual football in the film whatsoever, but I.D. faces a similar-sized struggle for verisimilitude as any on-pitch drama does. Many of the tense, scowling set-pieces and plot devices are based on supposedly real events in the experience of PC James Bannon, who went undercover with Millwall’s notorious Bushwhackers in the late 1980s.

Indeed, the officers’ first near-disastrous encounter with the suspicious hooligans borrows from Bannon’s anecdote of when his football-illiterate partner eagerly agreed in a Millwall pub that John Fashanu was a “lazy white c***”.

How the fictional or real-life policemen managed to escape from either failed test of their credentials without compromising themselves there and then is conveniently ignored.

In a smart move to avoid the awkward task of creating a fictional place like Harchester or Melchester for its setting, I.D. instead awards a real one with a fictional football club: Shadwell Town – the Dogs – who proudly inhabit their ground known as the Kennel. Once again, it’s fairly easy to spot the inspiration, but the Shadwell Army emerge as a convincing enough set-up overall. Nearby London district Wapping acts as the hated local rival against whom Shadwell inevitably get drawn in the FA Cup, but the script doesn’t treat the fixture as a pivotal cinematic moment to unbalance the rest of the film.

Elsewhere, they come up against the “northern nonces” of “Pentland” before a coach-load of “Brummy bastards” arrive from “Midchester”. Once again, though, the film refuses to get bogged down in the hyperchoreographed side-street battles eventually seen in Green Street and the like. This is a psychological ride as much as a physical one, beginning with John (Reece Dinsdale) tentatively leading a chorus of “You’re Gonna Get Your Fucking Heads Kicked In” (which has its own Wikipedia page, I’m delighted to confirm):

As they continue their undercover groundwork, the officers engage in some credible-sounding banter while trying to bone up on Shadwell’s recent history:

“Nolan stuck Dempsey straight on the transfer list. Bournemouth had him. No, Portsmouth. £50,000. Good riddance to bad rubbish. Next season we draw Portsmouth in the Zenith Cup. No, Simod. And who scores against us? Bobby fucking Dempsey!”

It’s those little esoteric touches that steer the film away from too many potentially naff generalisations. One episode of terrace abuse towards one of their own hapless players – “Gerry Edwards”, who scores a free-kick shortly afterwards, and is immediately cheered to the rafters – perhaps veers the wrong side of fantasy: “You’re playing on drugs, and I don’t mean speed!”, our anti-hero quips.

YouTube has this scene in its entirety but, excellently, it’s dubbed into Italian for you to enjoy:

Anyway, the cast reads like a prescient Who’s Who of the British Soap Awards, to the point where part of the film’s appeal is pointing at someone, as they break someone’s face with a crowbar on CCTV footage, and exclaiming “Look! That’s the dad from the Inbetweeners!”

Elsewhere, there’s Billy from EastEnders, one of the old GPs from Albert Square that wasn’t Dr Legg, the other one from Life on Mars, the mum from Outnumbered, Warren Clarke’s glaring pub landlord (who, for some reason, like Yoda constructs his sentences) and Sean “son of Doctor Who, voice of Masterchef” Pertwee. The Shadwell Army.

The bespectacled, by-the-book detective sergeant Trevor (Richard Graham) is a star turn in a supporting role. He repeatedly comes close to compromising their cover after a few pints settle him rather too comfortably into his well-researched identity: “Reckon you’re Shadwell? Name every goalkeeper since World War One,” he slurs. “I can.”

"Get your tools out, get your tools out, get your tools out for the lads! Get your tools out for the lads!"#Gumbo pic.twitter.com/rTlpOsmurW

— I.D. Quotes (@Shadwelldogs) July 7, 2013

Among the blissfully unaware hooligan footsoldiers is the nervous wreck Gumbo – the film’s enduring and endearing cult hero, who jars gherkins for a living and who everyone “fucking loves” at one point or another – and, for some reason, a fire-eating extra who’s wandered in from a Dexy’s Midnight Runners video.

Their signature chant (“Shadwell never, never, never shall lose face”) is the unofficial theme song – dubbed here into Spanish, obviously:

That just leaves Dinsdale’s exceptional turn as detective constable John Brandon – for which he [citation needed] won the International Critics Award [citation seriously needed] for Best Actor at the Geneva Film Festival [oh, come on].

He’s armed with a steely glare, a quick brain and a sprinkling of charm whenever Lynda’s pouring the pints at The Rock.

John’s 90-minute conversion from ambitious, happily-married copper to adrenaline-addicted top boy with an arse tattoo is predictable, yet compelling.

The mise en scène is completed by some appropriately gritty location choices – a Millmoor here, a Valley Parade there – to provide the dystopian footballing backdrops for the violence and police malpractice. An ominous score composed by Will Gregory of eventual Goldfrapp fame (seriously, everyone’s involved in this film) finishes off the whole menacing feel rather well. Its writer Vincent O’Connell, however, was aiming for something rather grander:

“It’s no secret I was unhappy at how this film turned out. I kept quiet at the time it was released, not talking to the press and so on, but I was in grief that a powerful cinematic vision had come out looking like a standard bit of British TV social realism. I’d trusted Phil Davis to direct it as he is such a superb actor, and this film had to stand or fall on the central performance, but he just couldn’t see the cinematic potential of the script.”

Not that I.D. is a relentlessly grim affair. It’s joyously quotable, which is surely a huge part of its cult status, and the rapport John builds with the Shadwell hooligans (and, initially, with his undercover colleagues) can be genuinely charming, which indirectly explains why he gets so wrapped up in it all.

His cover stories include naming his only child – “James Wilson Hibbin Chatfield Edwards Hutchison Clark Edmonds Ball Cox Cummins” – after a recent promotion-winning Shadwell starting XI.

My kingdom for fictional club Shadwell Town's 1988/89 home shirt. pic.twitter.com/ecEvNMgfYt

— Adam Hurrey (@FootballCliches) November 29, 2014

A sequel to I.D. took 20 years to emerge, but it’s a disappointment for any confirmed fans of the original – albeit not on the scale of the unfathomable straight-to-DVD abominations Green Street 2: Stand Your Ground and Green Street 3: Never Back Down. By 2015, Shadwell have been taken over by a Russian oligarch (yes, seriously) and the Dogs are preparing for a European tour. What all that means for The Rock is unclear, but east London gentrification has presumably turned it into a craft beer place that serves cupcakes on a slate.

O’Connell, even if his original vision for the film wasn’t realised, has been reassured by the film’s cult following.

“My view has slightly mellowed over the years, as people keep telling me what a good film it was, and I see the excitement that generations of students especially have expressed about it. Middle-aged men have tattooed quotes from the film on their bodies, and teenage student women have parties to watch it.”

With the police investigation eventually closed, and John’s life in tatters, I.D. still manages to leave us with an ambiguous ending, which avoids tying things up too nicely: football hooligan films, by definition, should surely be that rough around the edges.